Edible Bird’s Nest is more than Just Soup and Dessert

Posted on

Introduction

There are more than twenty four species of swift distributed around the world, but only a few species that produce nests that are deemed edible. The majority of edible bird’s nests consumed worldwide come from two species, namely Aerodramus fuciphogus and Aerodramus maximus . They can be found in areas covering Nicobar Islands, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia, Borneo and Palawan Island in Philippines.

Malaysia is estimated to produce about 350 MT of edible bird’s nest annually, and is mainly harvested in specially-designed bird houses which scatter throughout the country. The price of edible bird’s nest has been influenced by many documentaries in media channels such as National Geography showing harvesters, hanging high in caves in Thailand and Borneo, to harvest edible bird’s nest in caves. The harvesting of edible bird’s nest is dangerous, thus the justification of its price. A kilogram of edible bird’s nest in soap or consumed as sweet dessert with rock sugar will set diners back by about RM10,000 in high-end Chinese restaurants in Kuala Lumpur, Hong Kong and Singapore. The burgeoning economy in China had also spurred a high demand for edible bird’s nest which is given as a gift to cement business deals.

Bioactive Peptides from Edible Bird’s Nest

Edible bird’s nest is the nest of the swift that is formed from its coagulated saliva. In the nest, a pair of swift would raise a chick. The harvester would wait until the chick could fly before harvesting the edible bird’s nest. In effect, the harvester is providing a safe place for the swift to raise its young. Thus, the harvesting of edible bird nest is less harmful than the production of the more expensive food, i.e., caviar. In order to harvest caviar, the fish, sturgeon, had to be killed to extract the roes, which is caviar.

Studies by researchers at Malaysian universities have discovered key bioactive peptides from enzymatic hydrolysis of proteins of edible bird’s nest. The primary purpose of protein consumption is to provide essential amino acids, which are used by the body to synthesize various structural proteins required for homeostasis maintenance. However, the increasing popularity of functional foods and nutraceuticals has led scientists to seek protein-derived peptides that could prevent or even treat metabolic disorders.

The ability of these peptides to influence biological reactions and physiological conditions is what makes them “bioactive”. A bioactive peptide consists of a certain number of amino acids (2-20) that are usually encrypted within the linear protein chain and remain inactive until released by digestion. Thus, it follows that appropriate gastrointestinal tract (GIT) digestion conditions, food proteins could yield bioactive peptides. Peptide absorption from the GIT is then facilitated by specific or non-specific transporters, cellular endocytosis and simple translocation (passive diffusion) into the blood circulatory system. However, the level of such bioactive peptide release during food digestion is considered very low and of little consequence to human health.

Therefore the most useful approach involves customized in-vitro protein digestion with human or proteases in order to enhance bioactive peptide production. Upon completion of the enzymatic hydrolysis, the digest is centrifuged and the soluble portion is isolated as the protein hydrolysate while the undigested portion is discarded. High peptide solubility increases absorption potential during oral consumption.

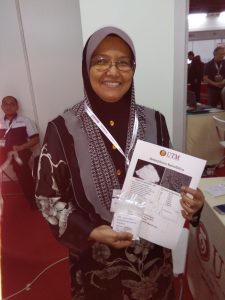

A research group at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, led by Professor Dr Abdul Salam Babji, had tested the desirable activity of bioactive peptides from edible bird’s nest. They include antihypertensive and antioxidant.

Apart from the demonstrated health benefits, one of the main attractions of food protein- derived peptides is the low risk of negative side effects that are normally associated with drug therapy. Therefore, even though peptides are less active on a weight basis, they can be used as preventive or therapeutic agents as relatively higher doses than possible with drugs. The relative safety of food protein-derived peptides may be attributed to faster clearance from the blood circulatory system since they susceptible to peptidase-dependent degradation. Moreover, unlike drugs, peptides are not stored “as is” in tissues but are rather used for the biosynthesis of new protein within the body. Unlike drugs, peptides do not require liver detoxification and are not excreted in the urine; therefore, potential damages to these organs are minimized during peptide therapy, even at high doses.

Bioactive peptides from edible bird nest have better bioavailability to be absorbed in the GIT as compared to the protein contained in the traditional edible bird’s nest soup. Traditional edible bird’s nest soup consumed together with its bioactive peptides should give better “value” to diners who pay for this expensive coagulated sliver of a swift.

We recently enjoyed a bowl of edible bird’s nest with the edible bird’s nest peptides. It was delicious!!